” . . . All the Christs here are copied from Thorvaldsen’s [Christus] and look like Björn Borg.”

That was the conclusion of the French philosopher Jean Baudrillard, after visiting Salt Lake City. (See: Jean Baudrillard, America.). Like Alexis de Tocqueville before, in 1988 Baudrillard travelled through the United States to describe Americans as they were. Although not meant as a compliment, his comparing images of Jesus to a tennis champion was an important observation: Christ looked like a popular figure. Whether artists are aware or not of the phenomenon, the image of Christ is highly subject to the contemporary understandings of what the perfect man looks like.

A few years ago, I attended a meeting with a prominent Mormon art historian, one who regularly commissioned works on behalf of the Church. He told me:

“Mormon artists paint what God wants them to paint.”

When I asked what that meant, he replied

“They are earnest in seeking God’s will. As a result, God inspires them with images that align with His will.”

This argument is a medieval Christian adaptation of neoplatonic aesthetic theory that suggests an artist, in order to paint the truth, must be free from sin to receive inspiration. (This origins and developments of this theory are extensively charted by Erwin Panofsky in his book Idea.) Being worthy, the artist is not to copy directly from nature — the fallen, sinful world — but to appeal to God directly. (For an example, read “Rules for the Icon Painter,” PDF document.) The resulting eternal image should therefore avoid distortions of mortality. This notion of God placing an idea directly in the mind of an artist is particularly appealing to Mormonism, which espouses not just the possibility of personal revelation but the necessity of it.

When my art-historical friend suggested that Mormon artists are painting what God wants, he was not pleased with my response:

“If that’s true,” I replied, “then God must want us to buy lots of high-end electronics for Christmas.”

In retrospect, I was being patronizing like Baudrillard. My argument was: I am a good Christian — at least comparatively good to many others I know; I celebrate the Lord’s birth; this year, as part of my celebration, I bought an iPad for my children; therefore, God inspired me to buy the iPad. Its not a perfect argument. But, it is a an example of how difficult it is to avoid one’s time and place in one’s religious expression.

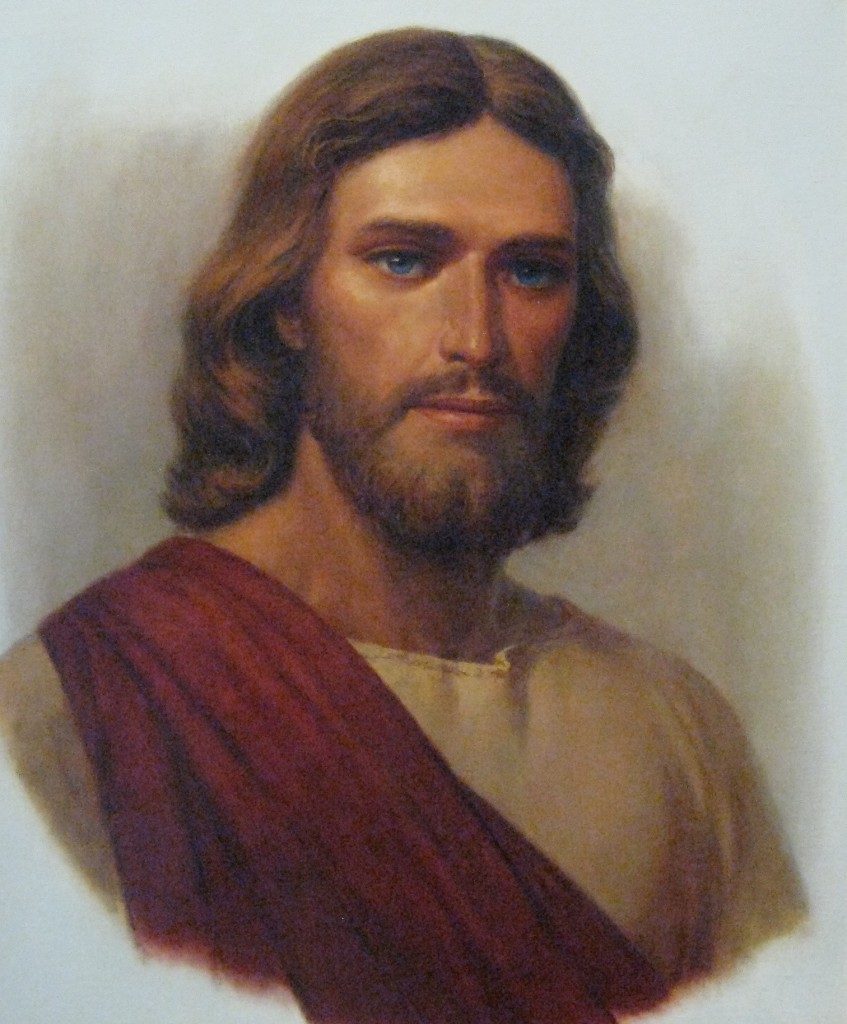

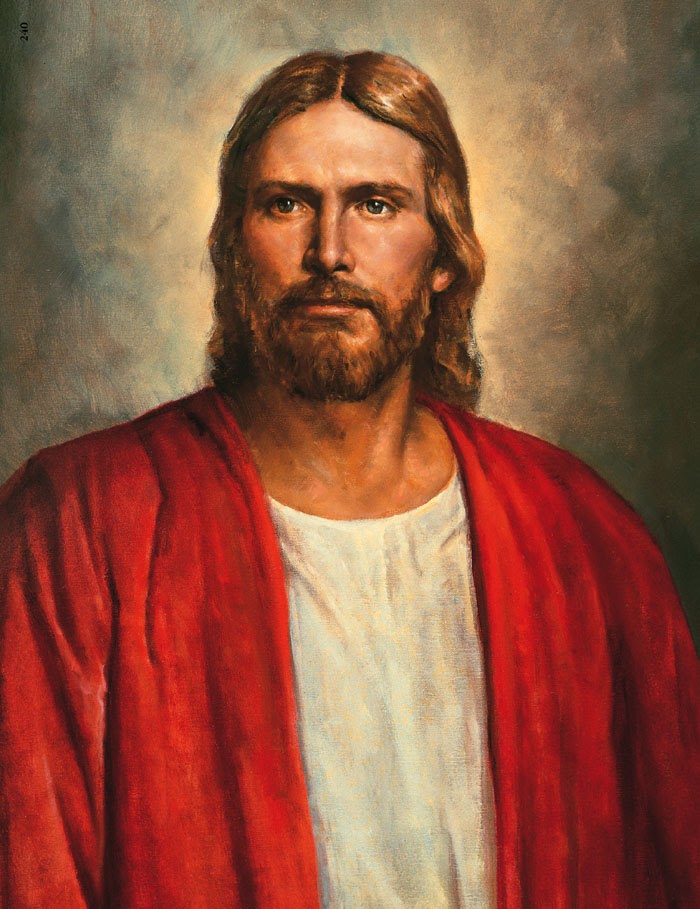

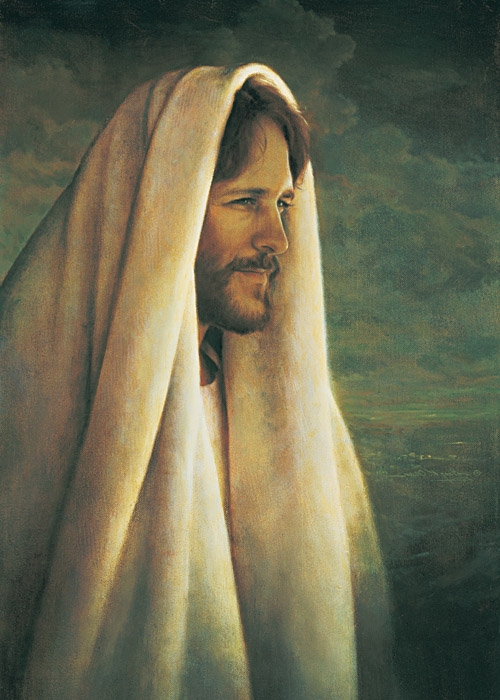

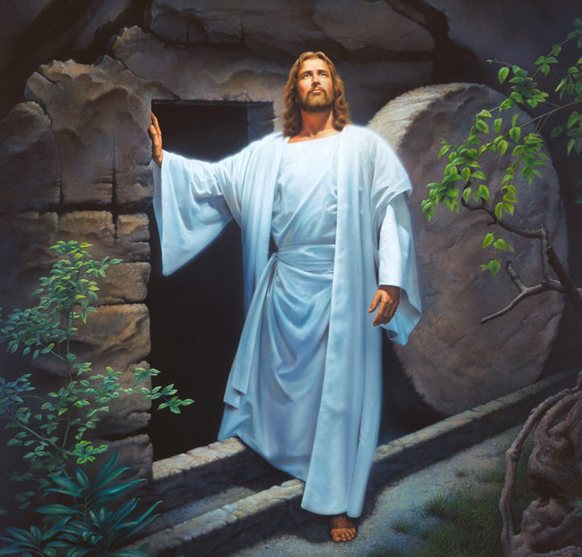

A better example is my experience visiting the 2009 Art & Spirituality Exhibition at the Springville Museum of Art. Held every year, it is perhaps the largest show of contemporary religious works in the country. Though the show often includes works by Hindu, Buddhist, and other Christian artists, the Museum’s location in Utah Valley and long association with Mormons means the preponderance of art submitted is LDS. At the exhibition in 2009, a special effort was made to invite prominent artists from years past, whose work was on display in the Museum’s largest gallery in chronological order from the mid 1970s to 2009. There were at least fifteen paintings of Christ by Mormon artists lining the wall. I’ve reproduced a few below.

The Christs painted in the 70s, or by artists of that era, looked like they were from the 70s. The hair was wispier and natural, the face slim, the face was thin. He could have been a member of ABBA.

The Christs painted in the 80s, or by artists of that era, looked like they were from the 80s. Some palettes turned from earth tones to electric blues.

The hair was tamed, including the beard which was closer to the face. The jawlines were stronger, not unlike Arnold Schwarzenegger, Sylvester Stallone, Tom Selleck, and Ronald Reagan, then prominent male role models.

The Christs painted in the 90s, or by artists of that era, looked like they were from the 90s. Christ became less rugged and more beautiful, even androgynous — think Brad Pitt and Tom Cruise, the decade’s pretty-boy leading men.

And, the Christs from the 2000s looked like they were from the 2000s. By this time, the figure of Christ took on a prominent v-shaped upper body, as if he had been weightlifting. But, he was not intimidating. In fact, the narratives changed too.

Rather than placing Christ in a three-quarters portrait, he began interacting with people more . . . hugging or offering to hug everyone n sight. It would be fascinating to correlate these depictions with the use of anti-depressants and the phrase “tender mercy.” If religion is the opium of the masses, then, for Mormons, Christ is becoming Prozac.

In other words, each Mormon’s depiction of Christ seem to be informed by the cultural understanding of the perfect man. It is why Jean Baudrillard could see a famous tennis player in Mormon art. The depiction of Christ is symptomatic of what we think and talk about; what we value. Have you ever seen a Mormon depiction of Christ pushing the moneylenders out the temple or the cursing the fig tree? I haven’t. Have you ever seen a Mormon crucifixion? I’m pretty sure we believe that He was crucified, although I have only seen one painting about it by Brian Kershisnik. How often do we talk about those subjects? I believe there is a directly relationship between what we talk about and what we paint.

This also affirms the notion that Mormons are not attempting to paint the historical Christ, who was mostly likely an olive-skinned, curly-haired semite. Neither are they depicting the Christ of scripture, who is usually described indirectly with symbolic language (i.e. “brightness above the sun,” “sound of rushing waters”). And, Mormon art makes no attempt to reconcile the very attractive man we depict with the notion that, according to Isaiah 53:2, “when we shall see him, there is no beauty that we should desire him.”

We then are left with the conclusion that by attempting to paint the perfect man, Mormon artists limit Him by their highly fluid understanding of perfection. That’s the negative way of saying it. Perhaps this is simply God speaking to Mormon artists “according to their language, unto their understanding.” (2 Nephi 31:3). Maybe God wanted artists to painted Bjorn Borg because the tennis champion conjures aspirations of greatness.

The question for me is not does the image of Christ change? Of course it does. The questions is: Can and should artists avoid that change? Should artists, and Mormons in general, embrace the notion that their understanding of Christ is constantly changing, and is both influenced by their religion and time? Maybe painting Christ is an extension of our understanding of Him; and, like, any other doctrine, the ability to understand or depict Him grows line upon line, precept upon precept . . . you know, like they sing in that timeless masterpiece Saturday’s Warrior.

These are some great thoughts and I think you’ve done well to point out the changing styles tied to changing times. In my experience as an artist it can be difficult to gauge the impact your immediate time has on your work. I think, for this reason, the classical tradition in religious art must be studied and emulated. Like with architecture, works done in a timeless style lend themselves to certain venues. This may help artists develop works that separate themselves from stylistic parroting current trends. Of course, as artists, we also have to be aware of our audience and consider the established icons of Christ. It would be impossible, for instance, to paint Christ as Michelangelo did, with shorter hair, no beard and blue eyes and still have that image communicate to today’s viewers.

On top of that, you have the cupcake and teddy bear market (Deseret Book, Seagull, etc.) that seems to drive the overly sentimental, soft and cheesy works of Christ. Most artists are like most people in that their concept of success is tied to money. So we see much of the artistic decisions pertaining to religious art conceding to these perceived demands by the average buying public, for the sake of a more sure sale (or mass sales when speaking of the print market). In these works we see artists using art as a mirror to reflect the average, luke-warm culture of the church. What we need are artists willing to use art as a hammer to forge new and lasting conceptions of what is, perhaps, the richest of all narratives.

This reminds me of Vasari’s comment that if you copy the hand of a Greco-Roman sculpture over and over again, you will eventually arrive at the perfect hand. That is perhaps the most succinct definition of neoplatonic thought applied to the fine arts. It is also the goal of most academic training. And, I believe that painting that hand over and over again will free the artist, in some measure, of contemporary influences and connect the artwork to a style that is more “timeless,” for lack of a better word. But, I still believe that the most classically trained artists are unwittingly influenced by their own time and place. I can look at a painting, regardless of the skill level of an artist, and usually date it within ten years. That is not an insult. It just is. I think that a classical education is more likely to make that work last beyond the contemporary trends that otherwise affect the work. Why? Because it has a language that transcends its own time, as well as being a part of its own time.

I am in total agreement. It is impossible to fully separate oneself from the influences of their own time. I have friends who are desperately trying, but the reality is our surroundings and interactions matter. I don’t think it’s necessary to try and defy those influences, as they are the source of our tangible reality. Our most sincere work will be an extension of that reality. But, like you say, a student of the classical tradition will be able to tailor their work in a manner that more fitfully transcends their own time. I think that this classical style, lends itself very well to this narrative.

Thank you again for putting these thoughts together. I think this type of art criticism is a needed system of checks and balances that has the potential to offset the current culture of mediocrity. As you covered in a previous post, artists achieving greatness and mastery have been prophesied. It’s unlikely to happen if all we do is pat each other on the back and congratulate ourselves. We’ve got to hold each other accountable and push each other to reach higher. Conversations like these are great. Thanks Micah.

I expect most, if not all, artists choose images of Christ that they can relate to. This is why their paintings reflect their times, race, etc. I know three artists who have strong muscular builds. Their interpretations of Christ look like them. I know another who’s version of Christ could pass for her own son. Artists have alway been influenced by their time and culture. What is wrong with that? Everyone is a critic.

I don’t know if there is anything wrong with artists painting their own time and culture. Seriously. It’s not just true of Mormons, it’s also true of Old Masters. Christs by Titian look like sixteenth-century Venetian lords. Christs by Rubens look like Northern Europeans. I guess my only reason for pointing it out is that we need to be aware of the phenomenon.

I found your comments on what kind of depictions of Christ we don’t usually see, such as the crucifixion, cleansing of the temple, and cursing of the fig tree, to be fascinating. The main crucifixion piece that I think of is the Harry Anderson one, but I couldn’t think of anything more recent. I did a little searching, and I did find one by Simon Dewey of all people, though it just shows the mourners at the cross and a shadow of the cross looming over them. As for the cleansing of the temple, I imagine the depiction would be similar to the most recent official Church Bible video of that incident, which is fairly underwhelming. If I remember correctly, Jesus just walks through the temple, turns a table over, knocks over a couple things, and makes a proclamation. Not really that exciting.

But that’s just an indication of what we’re comfortable with in our depictions of Jesus. I think the consensus in the other comments is that there’s nothing wrong with people in different eras depicting Jesus in different ways, as long as we acknowledge the fact that we’re doing it. I tend to agree, and I think acknowledging it not only helps us understand what’s really going on, but will help us to look at what the depictions show about how the artists themselves and we as a Church view Jesus Christ.

The problem, however, is that sometimes we give Christian and especially Mormon artists some kind of legendary status, like God is putting images directly in their minds of what Jesus *really* looks like, and they just put it on a canvas. I think those with a knowledge of art history will know what’s going on, because it’s been going on for hundreds of years. Unfortunately, it’s difficult to teach an entire church a course in art history so that they can understand the real significance of what they’re looking at.