It has been nearly three decades since Spencer W. Kimball’s address “The Gospel Vision of the Arts.” Speaking of the possibilities for LDS arts he spoke optimistically:

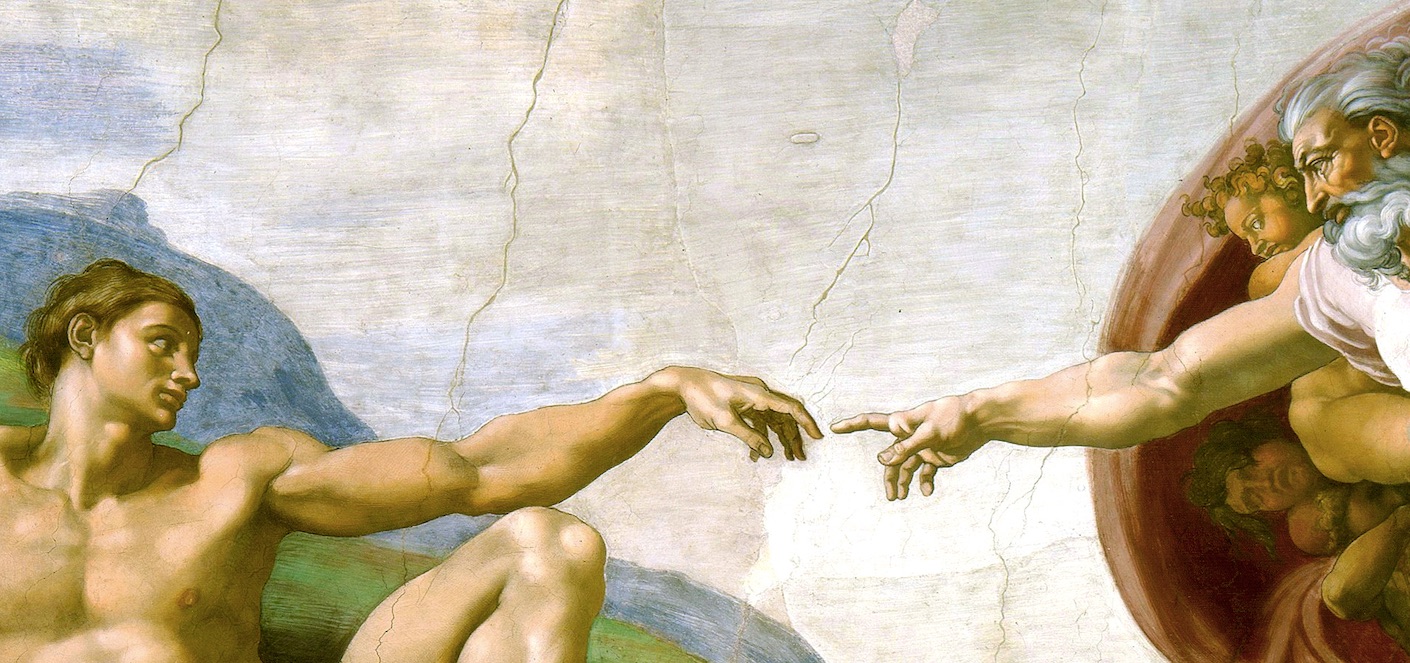

Take a da Vinci or a Michelangelo or a Shakespeare and give him a total knowledge of the plan of salvation of God and personal revelation and cleanse him, and then take a look at the statues he will carve and the mural he will paint and the masterpieces he will produce.

(Spencer W. Kimball. “The Gospel Vision of the Arts.” SOURCE HERE.)

This has caused many members of the Church to speculate on when or where a “Mormon Michelangelo” would appear. (Will it be a graduate of BYU’s Illustration Department? “The horror!” says an abstract installation artist working in the Studio Program.)

MORMON MEDICI?

I believe that focusing on the artist is premature. Long before da Vinci or Michelangelo, in Italy there was a dynamic culture of patronizing painters, sculptors, and architects that were — at first — considered little more than craftsman. But as the highly competitive and intellectual tastes of the Florentine, Venetian, Neapolitan, and Roman elite increased, so did the status and output of artists.

So whenever I hear the question “Where is the Mormon Michelangelo?” I want to ask: “Where are the Mormon Medici?” The current market for Mormon art and purchasing practices of the Church will be described at length in future posts, but it is clear to me that we are not yet at Renaissance levels of investment epitomized by the Medici family, who bankrolled many of Michelangelo’s projects, not to mention many other artists of the time.

A MORMON SISTINE CHAPEL?

If we eventually have a well funded Renaissance, it begs another question: Where would we put the resulting art? Do we have the equivalent of a Sistine Chapel ceiling, ready to be painted with The Creation and Last Judgment? The answer is not simple.

Some of the most sacred places in Mormondom are visual deserts, deliberately void and denuded of strong figurative art. I have never seen a work of art in a Celestial room. And the remaining interior real estate of temples tends to be dominated by landscapes, with and occasional original or giclée reproduction of figurative works. The same may be said for chapels. With the exception of only two early-twentieth-century ward houses, I have never seen a meetinghouse with a painting larger than a chalkboard, let alone a work of art within the sacrament meeting room.

Why?

It is my guess that if one were to enter the Celestial Room and see Michelangelo’s expansive, colorful, multi-figural Sistine Chapel ceiling — or its Mormon equivalent full of modestly-clothed, de-winged angels — it would potentially be a huge distraction from the rituals of the temple. Celestial rooms are deliberately non-distracting environments. Even the furniture is often white.

The same is true for a sacrament meeting. Members are meant to focus on the revealed words of the sacrament prayer; not a visual representation of it. In this sense, Mormons may be considered iconoclasts.

So my questions are:

1. Where are the Mormon Medici?

2. In what venue would Mormons display their version of the Sistine Chapel?

I think that one more point you overlooked before we answer either question is the “why”. My understanding is that many Renaissance catholic pieces were depicted to teach scriptural stories to an uneducated or illiterate (non-Latin speaking) audience. Do Mormons need to be taught visually? I don’t necessarily think so. But I do think it could only add to our grasp on doctrine and culture. We first need to realize that we can learn in more ways than reading scriptures and talks. And take the time in our lives to reflect on visual representations for a time.

I have had the same thoughts many times. Achievement in art must be funded somehow or it is not likely to happen. However, when the Medici’s chose to funnel their money into the arts, they had great craftsman to choose from. Michelangelo may have been a great talent, but without proper training and development, he may have ended up repairing the cobble stone streets of Florence instead of creating the Pieta. It may be a chicken or the egg question. Do you need the money first, or artists worthy of it? I don’t know the answer, but it seems to me that one problem we face today is the desire for immediate answers instead of the fostering of a significant and perpetual system. Much of the money spent now is spent on ‘established’ artists who are known to the decision makers. Usually not particularly well developed talents, but popular in the right crowd. It leads to, as Adam said, uneven quality. Proper training for artists is, as it always has been, the key to unlocking the potential for great works. There is debate among the untrained on what proper training is. But, there is no denying the effectiveness of how past masters trained. Name 5 LDS artists who have gone through that type of rigorous training and I’ll show you 5 worthy of Medici-like funding.

One more thought…..It is also true that few of the decision makers in the church have any knowledge of art or discernment between what is good and bad. There is also very little respect for artists as professionals. As an example, I was visited by a church representative who spent 4 hours in my studio telling me why I should do paintings for the temples. When I questioned the process of submitting works (which often takes months) and discussed how outside of normal professional practices the church process for purchasing work is, his flat response to me was, “You have to understand that you are not in a respectable profession”. If great artists are to create great things, they must be extended the professional trust, courtesy and monetary value that they have worked to earn. While no artist should approach the church with expectations of achieving great wealth, the church must understand that the investment an artist makes is huge and any work of art they produce is only possible after the many years of disciplined effort and logged hours prior to that particular work. We don’t pay artists well only for the one work purchased, but for their years of developed expertise.

I recently saw the murals that are going into the Downtown Provo Temple. They are of uneven quality. There are parts of them that are stunning, and parts that induce head scratching. There is a great creation cosmos sequence that leads into a forest/lake setting–with palm trees in front of quaking aspen. There is a wonderful view of Mt. Timpanogoas looking North with the old Lake Bonneville spilling from Utah County into Salt Lake County with wild horses running through the grass–and there is a freaky big maned lion staring coldly out at the viewer with odd looking bunny rabbits looking up at him Eden-like. Clearly it was painted by committee with not all artists on the same page. I applaud the nearly million dollar investment into art, but we don’t have our Mormon Michelangelo yet. Here’s hoping for the next generation.

An intriguing question with a complex set of answers. Let’s start with this:

Church art is not objective. It is subjective. Art selection committees (often aided by so-called “art experts”) are typically made up of individuals whose liberal arts education called for the abandonment of traditional standards, values and practices. Operating under fixed budgets, such committees working for the Church do not have the freedom or the luxury of selecting the finest artists (the only exceptions of late are such long-dead artists as Thorvaldsen, Bloch and Hoffmann, partially I suppose because dead artists are so much easier to work with). Michelangelo made such a great contribution to the world in his day because no lower level committee person was authorized to tell him how and what he should draw, paint and sculpt. When the day comes that artists will be valued, recognized and honored as unique creative beings with special talents and gifts that have been rightly earned, and we are truly willing to trust their judgment and skills, and pay them accordingly, then we too will be worthy of having our own Michelangelo, Bernini, Ghiberti, Leonardo, Galileo, Ghirlandaio, Cellini, Giotto, Donatello, Raphael, the Della Robbia brothers and others doing comparable works. By the way, all these came into the world from a single small town of less than 100,000 and within the same relative time frame. Yes, times do change, but lasting values and true gifts from God never do. The world needs great art today just as much as any great civilization needed it before us. Perhaps we need to remind ourselves that in the end, our architecture and art are what truly distinguish us and define who we are as a civilization.

AN ADDENDUM

Unlike the Brigham Young of old who sent young artists to study from the European masters of his day, modern-day Mormonism doesn’t value ART and ARTISTS as transformative elements essential to life. To us, art is merely a visual aid, a teaching tool. Michelangelo’s Pieta, his portrayals of God, God’s Creation(s) and Final Judgement; Handel’s Messiah, Thorvaldsen’s Christus and Bloch’s interpretation of the Living Scriptures move us to tears. Why? Because such creations were not intended to serve as propaganda. Rather, they stand as a living, lasting witness of God, God’s creations and Man’s divine creative potential. The reason these works are so moving, so deeply inspirational and life-changing is because thy cause the nerve synapses to finally connect our hearts and our brains to our souls.

Understandably, we have adopted Bertel Thorvaldsen’s Lutheran image of Christ as if we created it with our own hands. Now an iconic symbol of our own religion, we use it in part to irrevocably affirm our own direct connection to Jesus Christ. How much better might Thorvalden’s depiction of Christ and the Twelve Apostles had been if only he had had the “Gospel in all its fullness?” In reality, we do have living artists walking among us today who are potentially just as capable as many of the great masters of the past. But as a matter of institutional policy, how do we choose to treat them?

Edward, this was beautifully written. Thanks for your thoughts. I completely agree.