” . . . All the Christs here are copied from Thorvaldsen’s [Christus] and look like Björn Borg.”

That was the conclusion of the French philosopher Jean Baudrillard, after visiting Salt Lake City. (See: Jean Baudrillard, America.). Like Alexis de Tocqueville before, in 1988 Baudrillard travelled through the United States to describe Americans as they were. Although not meant as a compliment, his comparing images of Jesus to a tennis champion was an important observation: Christ looked like a popular figure. Whether artists are aware or not of the phenomenon, the image of Christ is highly subject to the contemporary understandings of what the perfect man looks like.

A few years ago, I attended a meeting with a prominent Mormon art historian, one who regularly commissioned works on behalf of the Church. He told me:

“Mormon artists paint what God wants them to paint.”

When I asked what that meant, he replied

“They are earnest in seeking God’s will. As a result, God inspires them with images that align with His will.”

This argument is a medieval Christian adaptation of neoplatonic aesthetic theory that suggests an artist, in order to paint the truth, must be free from sin to receive inspiration. (This origins and developments of this theory are extensively charted by Erwin Panofsky in his book Idea.) Being worthy, the artist is not to copy directly from nature — the fallen, sinful world — but to appeal to God directly. (For an example, read “Rules for the Icon Painter,” PDF document.) The resulting eternal image should therefore avoid distortions of mortality. This notion of God placing an idea directly in the mind of an artist is particularly appealing to Mormonism, which espouses not just the possibility of personal revelation but the necessity of it.

When my art-historical friend suggested that Mormon artists are painting what God wants, he was not pleased with my response:

“If that’s true,” I replied, “then God must want us to buy lots of high-end electronics for Christmas.”

In retrospect, I was being patronizing like Baudrillard. My argument was: I am a good Christian — at least comparatively good to many others I know; I celebrate the Lord’s birth; this year, as part of my celebration, I bought an iPad for my children; therefore, God inspired me to buy the iPad. Its not a perfect argument. But, it is a an example of how difficult it is to avoid one’s time and place in one’s religious expression.

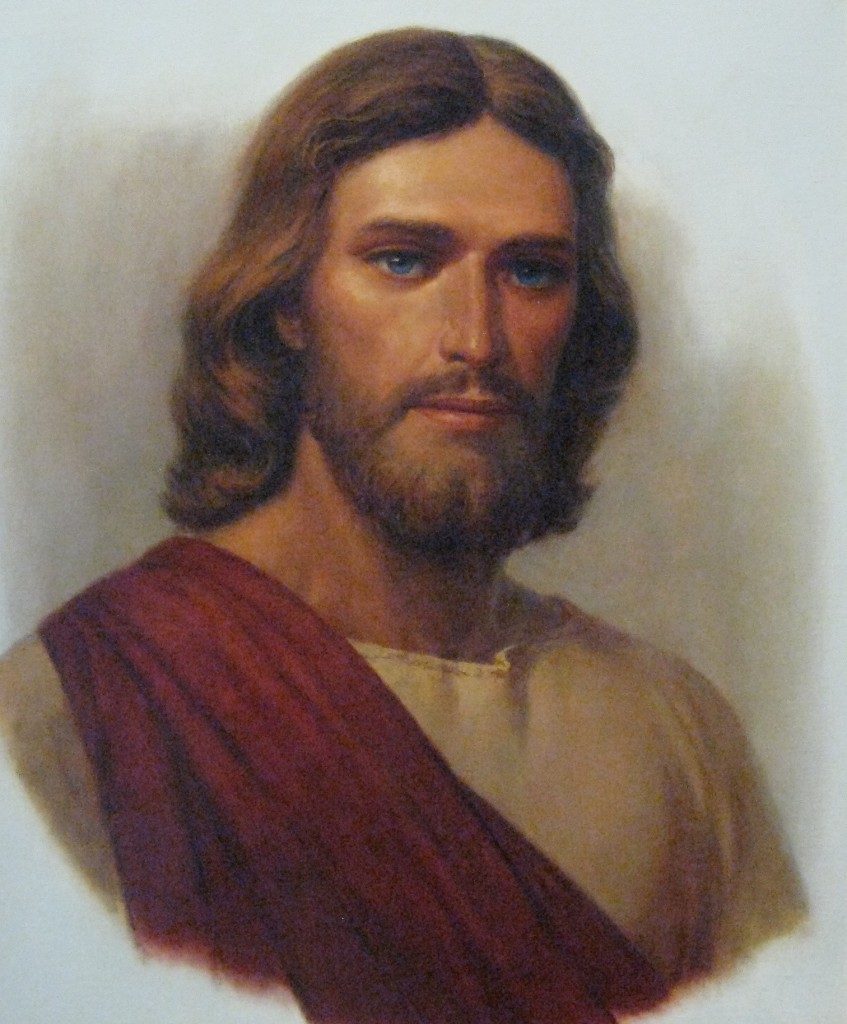

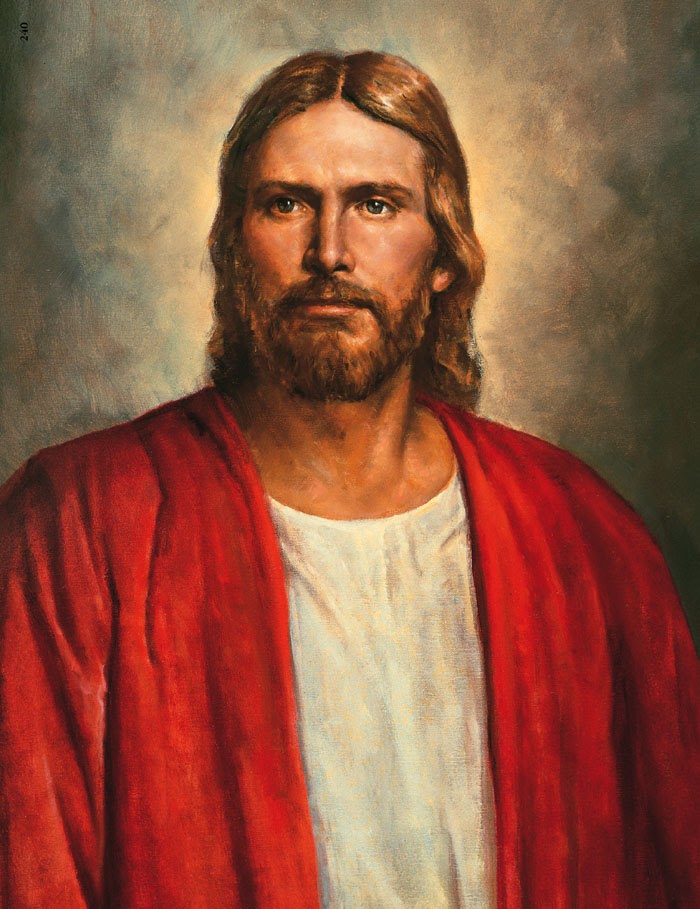

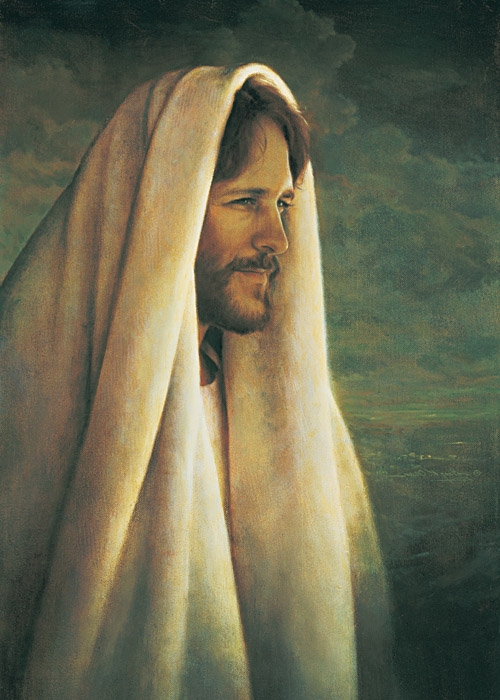

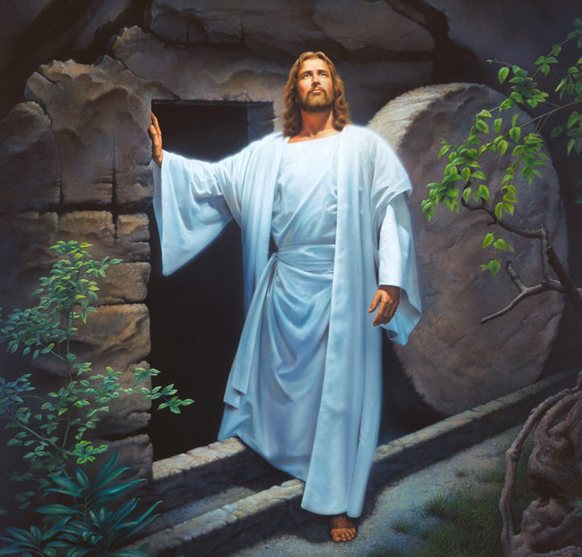

A better example is my experience visiting the 2009 Art & Spirituality Exhibition at the Springville Museum of Art. Held every year, it is perhaps the largest show of contemporary religious works in the country. Though the show often includes works by Hindu, Buddhist, and other Christian artists, the Museum’s location in Utah Valley and long association with Mormons means the preponderance of art submitted is LDS. At the exhibition in 2009, a special effort was made to invite prominent artists from years past, whose work was on display in the Museum’s largest gallery in chronological order from the mid 1970s to 2009. There were at least fifteen paintings of Christ by Mormon artists lining the wall. I’ve reproduced a few below.

The Christs painted in the 70s, or by artists of that era, looked like they were from the 70s. The hair was wispier and natural, the face slim, the face was thin. He could have been a member of ABBA.

The Christs painted in the 80s, or by artists of that era, looked like they were from the 80s. Some palettes turned from earth tones to electric blues.

The hair was tamed, including the beard which was closer to the face. The jawlines were stronger, not unlike Arnold Schwarzenegger, Sylvester Stallone, Tom Selleck, and Ronald Reagan, then prominent male role models.

The Christs painted in the 90s, or by artists of that era, looked like they were from the 90s. Christ became less rugged and more beautiful, even androgynous — think Brad Pitt and Tom Cruise, the decade’s pretty-boy leading men.

And, the Christs from the 2000s looked like they were from the 2000s. By this time, the figure of Christ took on a prominent v-shaped upper body, as if he had been weightlifting. But, he was not intimidating. In fact, the narratives changed too.

Rather than placing Christ in a three-quarters portrait, he began interacting with people more . . . hugging or offering to hug everyone n sight. It would be fascinating to correlate these depictions with the use of anti-depressants and the phrase “tender mercy.” If religion is the opium of the masses, then, for Mormons, Christ is becoming Prozac.

In other words, each Mormon’s depiction of Christ seem to be informed by the cultural understanding of the perfect man. It is why Jean Baudrillard could see a famous tennis player in Mormon art. The depiction of Christ is symptomatic of what we think and talk about; what we value. Have you ever seen a Mormon depiction of Christ pushing the moneylenders out the temple or the cursing the fig tree? I haven’t. Have you ever seen a Mormon crucifixion? I’m pretty sure we believe that He was crucified, although I have only seen one painting about it by Brian Kershisnik. How often do we talk about those subjects? I believe there is a directly relationship between what we talk about and what we paint.

This also affirms the notion that Mormons are not attempting to paint the historical Christ, who was mostly likely an olive-skinned, curly-haired semite. Neither are they depicting the Christ of scripture, who is usually described indirectly with symbolic language (i.e. “brightness above the sun,” “sound of rushing waters”). And, Mormon art makes no attempt to reconcile the very attractive man we depict with the notion that, according to Isaiah 53:2, “when we shall see him, there is no beauty that we should desire him.”

We then are left with the conclusion that by attempting to paint the perfect man, Mormon artists limit Him by their highly fluid understanding of perfection. That’s the negative way of saying it. Perhaps this is simply God speaking to Mormon artists “according to their language, unto their understanding.” (2 Nephi 31:3). Maybe God wanted artists to painted Bjorn Borg because the tennis champion conjures aspirations of greatness.

The question for me is not does the image of Christ change? Of course it does. The questions is: Can and should artists avoid that change? Should artists, and Mormons in general, embrace the notion that their understanding of Christ is constantly changing, and is both influenced by their religion and time? Maybe painting Christ is an extension of our understanding of Him; and, like, any other doctrine, the ability to understand or depict Him grows line upon line, precept upon precept . . . you know, like they sing in that timeless masterpiece Saturday’s Warrior.